Helen Frankenthaler: Painter, Printmaker, Sculptor, Ceramicist and Set Designer

Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) was an American artist whose illustrious career spanned the 1950s through to early 2000s. A painter, printmaker, sculptor, ceramicist and one-time set designer, Frankenthaler was, as the critic Barbara Rose wrote, a constant ‘experimenter with new media and techniques’. However, interest in Frankenthaler has often narrowly focussed on her vast, richly coloured paintings. Shedding light on Frankenthaler’s phenomenal body of woodcuts, Dulwich Picture Gallery’s exhibition Helen Frankenthaler: Radical Beauty prompts us to reconsider Frankenthaler’s practice outside of painting. Taking the exhibition as a starting point, I will explore the breadth of Frankenthaler’s oeuvre by highlighting a range of her works in different media.

Woodcut

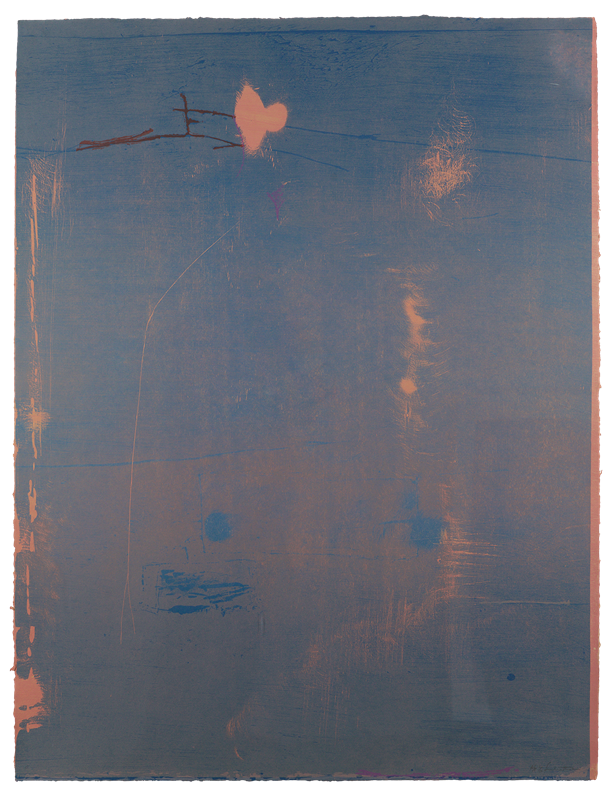

Frankenthaler began working in woodcut in 1973 and swiftly became enamoured with the medium. While woodcut was traditionally associated with harsh, graphic lines and rudimentary forms, in Frankenthaler’s hands it became a medium of new expressive potential. Collaborating with specialist print-making workshops, most notably Tyler Graphics Ltd., Frankenthaler invented several new woodcut-techniques which enabled her to create the painterly marks and nuanced surfaces. In Cameo (1980), a work included in Dulwich Picture Gallery’s exhibition, Frankenthaler creates a deep, velvety surface reminiscent of a night sky. The rich tonality of this woodcut is achieved through Frankenthaler’s layering of eight coloured pigments onto tinted paper. In Cameo, Frankenthaler also used a technique she had invented called ‘guzzying’ - where she distressed the surface of her woodblocks - to create the prints soft variated visual texture

Sculpture

During the summer of 1972, Frankenthaler made a surprising and playful group of steel sculptures. These sculptures are rarely discussed or exhibited yet there is a fascinating story behind their inception. In 1959, Frankenthaler met the celebrated British sculptor Anthony Caro during his first visit to America. The pair struck up a strong friendship and in 1972 Frankenthaler wrote to Caro suggesting that they made sculpture together. Frankenthaler subsequently came to London and spent two weeks working in Caro’s studio where she created a group of welded, steel sculptures inspired by her surroundings. Notably, Frankenthaler reflected that her sculpture Matisse Table (1972) ‘came out of those strong tea breaks in Tony’s [Anthony Caro’s] little office. There was a frayed Matisse poster announcement stuck on the wall and I’d stare at it. …I wanted to make my version of that Matisse table…’. Witty and geometric, Matisse Table reflects Frankenthaler’s sensitivity to form and, as Caro enthused, the ‘breath-taking freshness’ of her sculptures.

Ceramics

Frankenthaler experimented with ceramics between the mid 1960s and mid 1970s. Her work in this medium incorporates a mural in the lobby of North Central Bronx Hospital (1973-4), clay sculptures (1975), ceramic plates (1964), and tiles (1973). Arguably, Frankenthaler’s most successful work in ceramics was a group of tiles known as the Thanksgiving Day Series (1973). During the Thanksgiving weekend of 1973, Frankenthaler painted seventy-one ceramic tiles. Frankenthaler had been inspired to work in ceramics by Joan Miró’s ceramic mural at the Guggenheim Museum, New York. Like the uniform structure of Miró’s mural, every tile in Frankenthaler’s Thanksgiving Day series is the same shape and size, 34 x 44.5cm. However, each tile is an intimate and unique artwork: in Thanksgiving Day (#13), Frankenthaler juxtaposes pools of inky blue and turquoise with a loosely painted, linear scaffold.

Set Designer

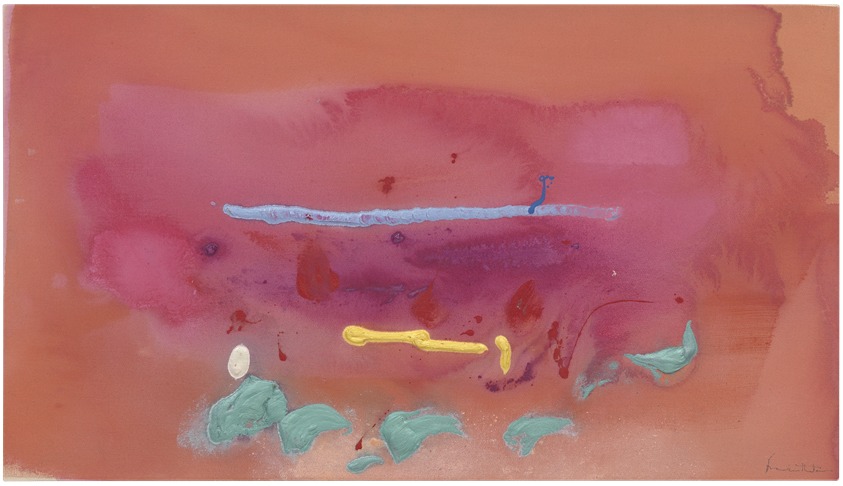

In 1985, Frankenthaler designed the sets and costumes for The Royal Ballet’s performance of Number Three, to the composer Sergei Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3, at the Royal Opera House in London. Frankenthaler became involved with the project after Bryan Robertson, who oversaw sets for the Royal Opera House, and Michael Corder, a Royal Ballet choreographer, visited Frankenthaler at her home and studio in Connecticut. While set design represented a leap from Frankenthaler’s previous work, she immersed herself in the process. In an interview with William Zimmer from 1985, Frankenthaler stated ‘I’ve bathed myself in the ballet. And when I’m there I’m looking at what color the wings are, what color the floors are…’. Frankenthaler created three backdrops for the ballet, each had an abstract scenic composition reminiscent of Frankenthaler’s contemporary paintings.

Cora Chalaby is a PhD candidate in History of Art at University College London. Cora’s research explores American abstract painting by women during the 1960s and 1970s, focussing on the work of Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, Howardena Pindell and Alma Thomas.

Twitter: @corachalaby

Images: Helen Frankenthaler, Cameo, AP 1/10 1980, Eight colour woodcut, Collection Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York. © 2021 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / DACS, London / Tyler, Helen Frankenthaler, Matisse Table, 1972, Steel, Collection Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York. © 2021 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / DACS, London, Helen Frankenthaler, Covent Garden Study: Final Maquette for Set, Third Movement, Ballet Number Three, 1984, Acrylic on Canvas, Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge.