Helen Frankenthaler and the American Print Renaissance

Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) is often associated with the movements of Abstract Expressionism and Colour Field Painting. While situating Frankenthaler’s practice in relation to these movements is chronologically useful, this has also led to a narrow view of her contribution to art histories. The rich body of woodcuts exhibited in Helen Frankenthaler: Radical Beauty positions her practice within an alternate art historical context: the American Print Renaissance.

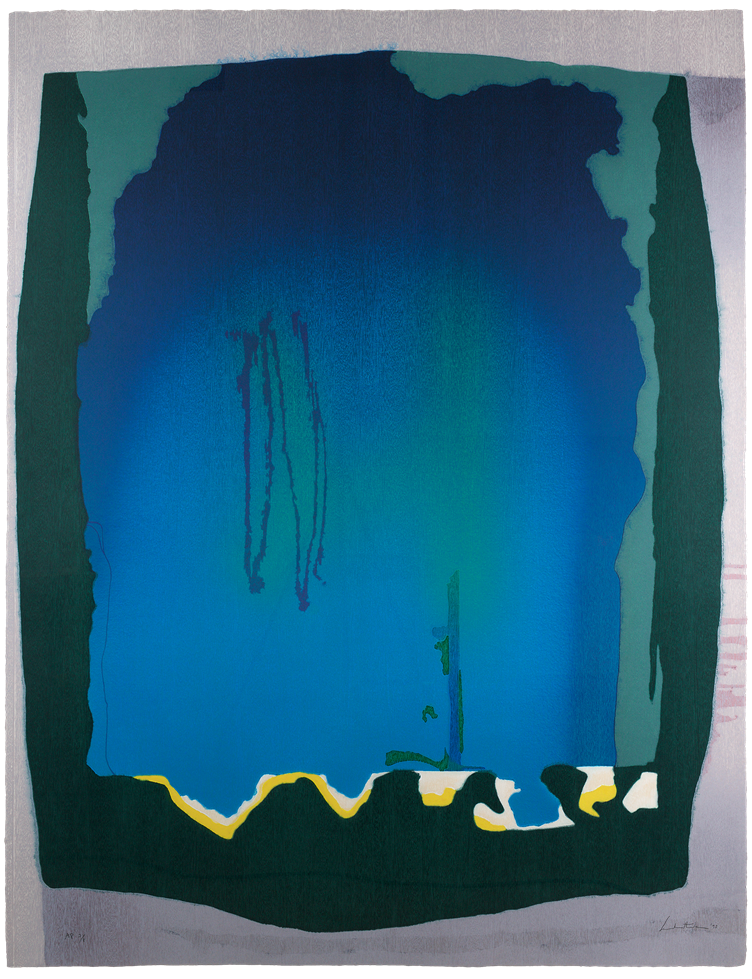

Helen Frankenthaler, Freefall, 1993. Twelve color woodcut from 1 plate of 21 Philippine Ribbon mahogany plywood blocks on hand-dyed paper in 15 colors, 199.4 x 153.7 cm Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York.

The American Print Renaissance spanned the mid-1940s to the late 1980s, which saw a revolution across printmaking media in the United States. In the early 20th century, printmaking was associated with commercial reproduction, cheap illustration, and small-scale graphic works. From the mid-1940s the aesthetic and function of printmaking radically changed. Printmaking transformed from a commercial craft to a legitimate medium of avante-garde production used by leading artists including Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, Jaspar Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg.

American prints of the second half of the 20th century are characterised by their innovative form, vast scale and vivid colour as demonstrated in Frankenthaler’s woodcuts such as Freefall (1993). Artists worked with master printers to develop radically new print techniques that reflected their abstract paintings. For example, in Tales of Genji (1998), Frankenthaler and the master printer Ken Tyler developed a technique of pouring diluted pigments onto plywood to create inky forms reminiscent of Frankenthaler’s ‘soak-stain’ paintings. Reflecting on the process of making this work, Ken Tyler recalled ‘the technique had no history. We were making it up as we went along’.

Helen Frankenthaler, Tales of Genji V, 1998. Forty-nine color woodcut from 21 blocks of maple and mahogany and one stencil on light rust TGL handmade paper, 106.7 x 119.4 cm

Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York.

The American Print Renaissance spanned the breadth of printmaking media, including lithography, woodcut, and screen-printing. Lithography, which involved drawing with grease ink and crayon onto a soft stone, was the first medium embraced by artists and workshops. Not only did lithography involve the least technical expertise but the fluidity of drawing in ink was seen as analogous to the fluid forms of abstract paintings by artists including Frankenthaler and Robert Motherwell. It was not until the late 1970s that woodcut, the oldest and most static of printmaking saw a revival. In the early 1980s the distinguished print scholar, Richard Field enthused: ‘the woodcut is back! Who could have imagined just ten years ago that serious art could be coaxed from such an obviously clumsy, totally antimodernist medium?’.

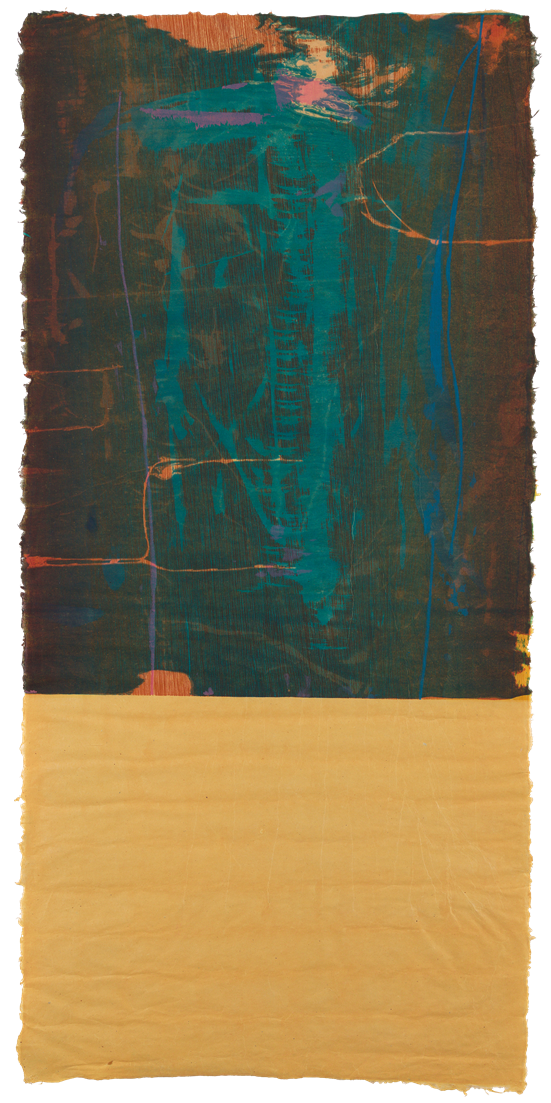

Field also praised Frankenthaler’s East and Beyond (1973) as the first of the ‘new breed of woodcut to capture public attention’. While Frankenthaler's greatest contribution to the American Print Renaissance was in woodcut, she looked across printmaking media to develop her innovative techniques. For example, the use of the Rainbow Roller, which Frankenthaler pioneered in Essence Mulberry (1977) had first been used in lithography by printmakers at the Universal Limited Art Editions workshop (ULAE).

Helen Frankenthaler, Essence Mulberry, Trial Proof 19, 1977. Woodcut proof of blocks 1 and 2, alternate block A, and uncorrected blocks 3 and 4, all inverted, printed on buff Maniai Gampi handmade paper, 100.3 x 47 cm, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York.

The increased affluence and education of American society in the 1950s and 1960s led to the emergence of a new middle-class audience eager to collect art. Prints, which are reproducible, were more affordable than monumental abstract paintings, and satisfied the needs of this burgeoning art market. The expanding market for prints corresponded with an increased confidence of artists and printmakers in producing experimental work within this medium.

The emergence of specialist artist printmaking workshops was also central to the development of the American Print Renaissance. The first artist printmaking workshop in the USA was Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17. Hayter’s emphasis on collaboration and innovation had an important legacy in subsequent workshops. In 1957 Tatyana Grossman opened Universal Limited Art Editions which has often been seen as the first major workshop of the American Print Renaissance. The prints produced at ULAE were distinguished by technically high standards and collaborative production. Frankenthaler made her earliest print, the lithograph First Stone (1961), and first woodcut East and Beyond (1973) at ULAE.

Following the success of Grossman’s ULAE, further specialist printmaking workshops opened in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. For example, Crown Point Press opened in 1962. Frankenthaler worked with Crown Point on her woodcut Cedar Hill (1983) which involved the specialist Japanese technique of ukiyo-e, or water-based printing. Meanwhile, in 1974, Ken Tyler opened Tyler Graphics, working closely with Frankenthaler from 1977-2000 on celebrated woodcuts included in Helen Frankenthaler: Radical Beauty including Essence Mulberry and Madame Butterfly (2000). Frankenthaler’s long-lasting relationship with the Tyler Graphics workshop was based on a shared commitment to innovation and a desire to test the possibilities of printmaking.

Kenneth Tyler, Helen Frankenthaler and Yasuyuki Shibata inspect proofs of 'Tales of Genji I' in the Tyler Graphics studio, 1997. Photo by Marabeth Cohen-Tyler, 1997, National Gallery of Australia.

Cora Chalaby is a PhD candidate in History of Art at University College London. Cora’s research explores American abstract painting by women during the 1960s and 1970s, focussing on the work of Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, Howardena Pindell and Alma Thomas.

Twitter: @corachalaby