For Your Pleasure

In this excerpt from In View, Curator Helen Hillyard explores one of Dulwich Picture Gallery’s most celebrated works by Antoine Watteau, an artist who had a profound influence on Berthe Morisot, the subject of our major exhibition, Berthe Morisot: Shaping Impressionism.

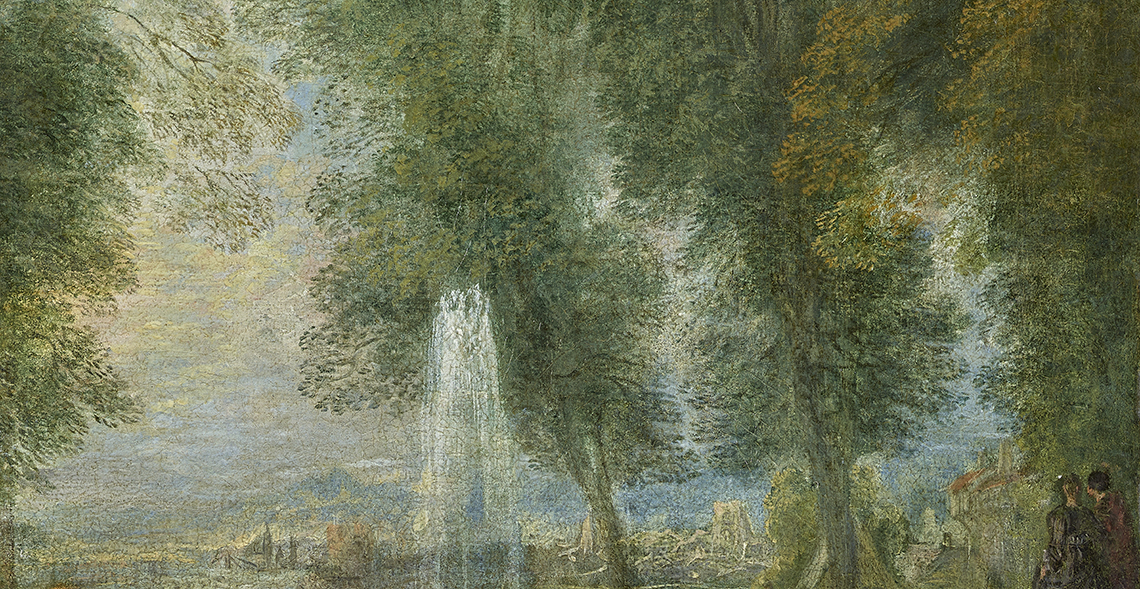

Watteau’s painting is set neither inside nor outside, instead occupying an in-between space. The classical architecture of a loggia (a sort of exterior terrace or corridor) gives way to a seemingly unending landscape. However, the grounds are less wild than they might at first appear, as just beyond the arch we can see the spray of an extravagant man-made water feature. Technical analysis shows that this quasi-outdoor setting was not part of Watteau’s initial plan, and that the artist’s first design for the composition had the scene taking place entirely indoors.

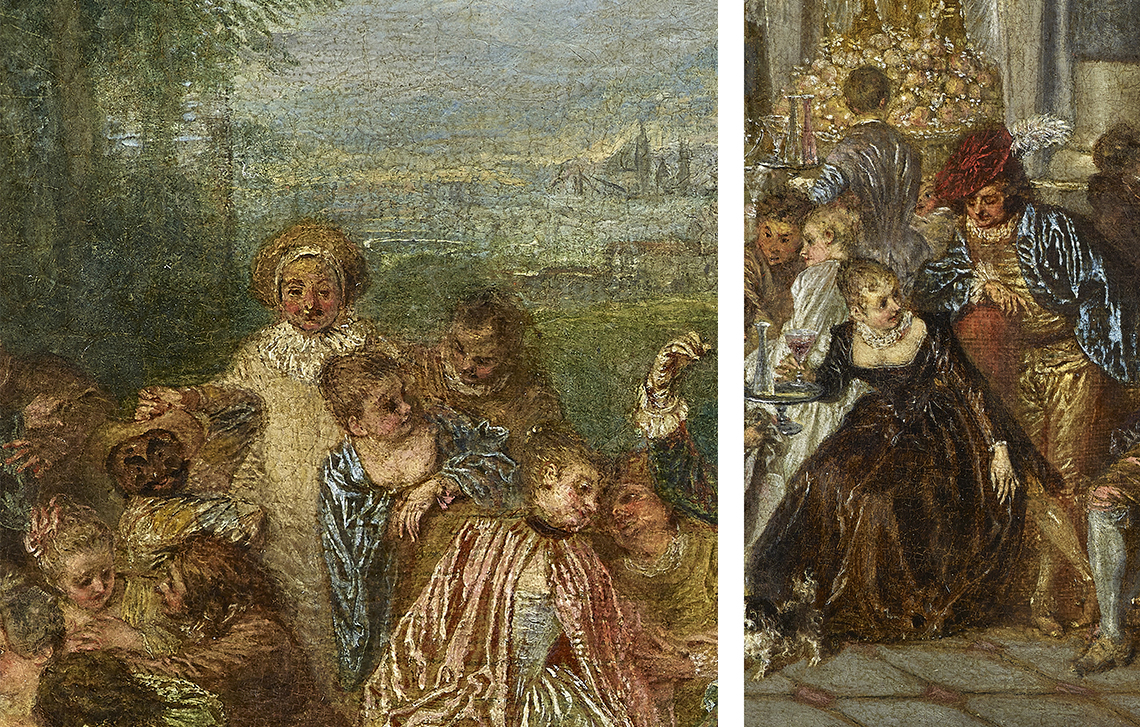

A Black figure, wearing a white, feathered turban, looks down upon the partygoers from a balcony. He is set apart from the action and, consequently, appears somewhat detached from the festivities. Watteau copied this particular figure from a painting by the 16th-century Italian artist, Veronese. Black servants, who were frequently enslaved individuals, were perceived as exotic and featured in European paintings as symbols of wealth, ownership and status. When depicted, they were often shown dressed in fanciful outfits, inspired by clothing of the Middle East and North Africa, although bearing little relation to reality.

The female dancer faces her partner, but keeps her back turned to us. She wears a fashionable “mantua”-style gown, characterised by its high, square neckline, small waist and full skirt. This was later known as the “Watteau gown” because it appears so frequently in the artist’s paintings. It is likely that the gown’s material, a striped silk, was made in Lyon, which was the primary centre for silk production in France. With gloved hands, the woman carefully lifts the hem of her skirt so as to allow for the movement of her feet during the dance.

With its stage-like setting, Antoine Watteau’s Les Plaisirs du Bal, c.1715–17, deliberately blurs the line between theatre and reality. To emphasise this, the artist includes several familiar figures from Commedia dell’arte, the early form of professional theatre originating in Italy and popular throughout Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries. Eighteenth-century viewers of the work would have immediately recognised one of its principal characters, Pierrot, dressed in white and wearing a large hat, hidden among the cavorting couples. Such details were undoubtedly included to delight and amuse those looking at the painting, only revealing themselves upon close inspection as a sort of 18th century version of Where’s Wally?

Watteau brilliantly captures the subtle signals and coy expressions that formed part of romantic and courtly life in 18th-century France. Fans were both an essential accessory and a vital tool for flirting. Typically constructed of painted silk, and often designed to complement a woman’s outfit, not only could they extend her hand gestures, she could use a fan to draw attention to her features, or shield a conversation with a partner from prying eyes.

This article was originally published in our Friends' magazine In View. To read the full magazine, pick up a copy of In View on your next visit to the Gallery or join as a Friend to receive yours free in the post.